Spyder’s Origins#

I started writing this post in October 2024, just after my talk at SciPy 2024, but I only finished it in January 2026. Better late than never!

How did Spyder come to be? What were the motivations behind its creation? In this post, I will answer these questions and more.

This post is basically the long textual version of the talk I gave at the SciPy 2024 conference (see my post SciPy 2024: My first SciPy conference). The talk was entitled “From Spyder to DataLab: 15 years of scientific software crafting in Python” and was part of the “General” track:

First contact with Python#

In 2007, I joined the CEA (the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission) as a research engineer. The team I worked with was using MATLAB for scientific computing. I was already quite familiar with MATLAB as it was the main tool used by students in my engineering school (SupOptique), but I had more experience with Mathematica at that time, following the research work I did during my PhD (2000-2003, on spectrally resolved numerical simulations of regenerative laser amplifiers). Anyway, MATLAB was at the center of the team’s workflow ; we used it for device control, data acquisition, data processing, and visualization. MATLAB was both used as an interactive environment for R&D activities and as a platform for developing applications that were used by the team and by external users. For the latter, we used the MATLAB Compiler to create standalone applications that could be run without a MATLAB license on field computers dedicated to experiments. As those applications were used by non-experts, we had to provide a user-friendly interface, which was usually done using the MATLAB standard GUI features.

For R&D, MATLAB was and still is a great tool - let’s forget about the commercial aspects, or the proprietary nature of the language. It has tons of built-in functions, it is shipped with a powerful IDE, documentation is excellent, and the community is quite active. But, and it’s a big but, it was not suitable for developing applications that were to be used by non-experts. MATLAB’s GUI features were quite limited, and the applications we developed were not very user-friendly, not robust at all, and not reliable.

I remember a specific training session, in Autumn 2007, gathering all the team members and the non-expert users of our applications. We were testing the applications on the field computers with our cutting-edge scientific instruments, and it was a disaster. The applications were crashing, freezing, or not behaving as expected. I was particularly embarrassed because I was responsible for the software development part of the project. That was the turning point for me. I was convinced that there was a better way to develop applications, and I started looking for alternatives.

At that time, at the end of 2007, here is what I found:

Scilab was interesting but - in 2007 - it was not as powerful as MATLAB for scientific computing, and, at the same time, it had all the drawbacks of MATLAB for application development. Octave was not an option for similar reasons.

IDL was an appealing solution at first sight because of its powerful image processing and visualization capabilities (which were more advanced than MATLAB’s at that time). But, like MATLAB, it was not suitable for developing production applications (and also, the language was really dated).

Java was a good candidate, but the verbosity of the language was clearly at the opposite of what I was looking for: it was not suitable for concise and readable scientific code.

C++ was a good solution but not for rapid application development. It could only be used for industrializing the code, which was not my goal. I wanted a unique language for both R&D and application development.

F# was theoretically a good candidate because of its functional programming paradigm, and the fact that it combined the performance of a compiled language with the expressiveness of a scripting language. But, it was not mature enough at that time, and the community was very small.

Ruby was another good candidate, but the lack of scientific libraries was a showstopper.

Python was the perfect compromise. It was concise, readable, and had a large standard library. It was also easy to learn and to teach. But, at that time, it was not as popular as it is today, and it was not as powerful as MATLAB for scientific computing. However, I was convinced that it was the right choice for developing applications that were to be used by non-experts.

After a careful evaluation of the alternatives, including discussions with a Python expert of another Department at the CEA (High Performance Computing, where Python was already used but for very different purposes: mainly preprocessing and postprocessing of simulation data, on Linux), I submitted a proposal to the Head of the Laboratory to switch from MATLAB to Python for developing applications. The proposal was accepted despite the fact that I was the only one in a 300-people Department to know Python (and I was not an expert at all), and that I clearly stated that it would mean to stop releasing new applications for 1 to 2 years - in retrospect, it was a very bold move, and I was very glad for the vote of confidence from the Head of the Laboratory.

However, in 2007, Python was not as accessible as it is today. There was no ready-to-use integrated environment like MATLAB. Choosing the right GUI library was not as straightforward as it is today, and scientific libraries were not as full-fledged as they are today. So, there were a lot of challenges to overcome…

About Python libraries#

Coming from the MATLAB world, the Python language itself and its standard library was so intellectually refreshing. Everything seemed more natural and more consistent. Possibilities were endless.

For scientific computing, NumPy and SciPy were delivering the basics - some functions were missing, but this was the opportunity to learn that it was extremely easy to write C/C++ extensions (or even simpler: Fortran extensions, thanks to f2py). In other words, there was no blocking issue, only opportunities to learn new things, in a very stimulating environment. And, as a bonus, the community was very active and very helpful.

For graphical user interfaces, the choice was not as obvious as it is today for desktop applications. Tkinter was the standard GUI library, but it was not as powerful as PyQt. There was also wxPython, but the code was terrible to read and was not as robust as PyQt. Another alternative was PyGTK, but it was not as portable as PyQt: support was great on Linux, but not on Windows (our main target). So, the choice was clear: PyQt was the way to go. History proved us right: Qt is still the best choice for desktop applications in Python.

For data visualization, the landscape was obviously quite different as it is today but, actually, the situation is not that different for desktop applications (web applications were almost non-existent at that time):

Matplotlib was the standard for 2D plotting, but it had the same limitations as MATLAB in terms of performance and interactivity. It was a very powerful library with tons of features, but designed for static plots (e.g. publication-quality plots). It was not suitable for interactive data exploration in the field of image processing. Try to show a 10,000x10,000 image with Matplotlib, then zoom in and pan: it was a disaster, and it still is.

PyQwt was a good alternative for 2D plotting, but it was not as powerful as Matplotlib. It was based on Qwt, a C++ library, and was not as flexible as Matplotlib. But it was faster, much faster, and it was possible to implement user-defined interactions, plot items, and so on.

So, I decided to develop two new libraries:

guidata, for automatically generating graphical user interfaces based on the PyQt library. The objective was to define datasets (set of parameters) in the form of Python classes, and to automatically generate a GUI for editing these datasets. It was a very simple library, but it was very powerful for generating user-friendly interfaces for non-experts. The idea was similar to the traits library, but without the Enthought tentacular ecosystem.

guiqwt (which has been replaced by plotpy in 2023), for interactive 2D data visualization based on the PyQt library. It was first based on PyQwt, then I was forced to reimplement PyQwt in pure Python in 2014 because it was not maintained anymore - this led to the creation of PythonQwt. The objective was to provide a library capable of plotting curves with hundreds of thousands of points, as well as big images, with interactive features like zooming, panning, and so on. Moreover, we needed to be able to transform image data in real-time - for that, we developed a C++ extension that was able to perform complex image processing operations in real-time (interpolation, antialiasing, affine transformations, etc.).

Note

The PlotPyStack organization was created in 2023 to regroup PythonQwt, guidata and plotpy. The idea was to provide a coherent set of libraries for developing scientific applications in Python.

DataLab is a great example of what can be done with these libraries. It is an open-source platform for signal and image processing and visualization, leveraging the GUI generation capabilities of guidata (for editing processing parameters, for example) and the interactive visualization capabilities of plotpy.

It took one year and a half to develop the initial version of these libraries, and to create the first applications based on them. The first application was a standalone neutron spectroscopy application for controlling scintillator detectors, acquiring data, processing it, and visualizing it. At the end of 2009, this application was put into production and was used by the team and by external users. It was a great success for the team, the best reward I could have hoped for after all the efforts I put into it and the risks I took.

This first internal production software was also a good demonstration of the power of Python for developing scientific applications. The first step of a journey that would lead to the widespread adoption of Python at the CEA: after that, I founded a Python user group at the CEA, organized training sessions, conferences with external speakers, and so on. But that’s another story…

About distributions#

As I mentioned earlier, one of the key strength of MATLAB was the integration of all the tools in a single environment. Working with MATLAB only required to execute the all-in-one installer, and everything was ready to use: the Integrated Development Environment (IDE), the features (processing, visualization, etc.), and the documentation. Everything was distributed in a single package, and everything was consistent.

The equivalent for Python was not as straightforward. There was only one distribution that was close to what we were looking for, and it was Enthought Python Distribution (EPD). It was a commercial distribution, but it was the only one that was providing a complete environment for scientific computing. It was also shipped with Matplotlib, NumPy, SciPy, PyQt, and many other libraries. It was a great distribution, but it was not free, and it was not open-source. And, more importantly, it was not a real all-in-one solution for Windows users: it was not providing a good IDE, and it was not providing a good documentation system, nor a good integration in the Windows environment.

That’s why I decided to create a new distribution from scratch, named Python(x,y). The idea was to provide a free and open-source distribution that would be as close as possible to the MATLAB environment. The distribution was first shipped with Eclipse and Pydev for the IDE (in 2008), and later with Spyder (starting from 2009).

It was just a few months after I even heard about Python that I started developing this distribution. It was a crazy idea, but it was the only way to make Python accessible to non-experts. And it was a great success.

💡 Talking about craziness, when I look back to this period, it was a bold move to start such a distribution project simply because there was nothing comparable at the time. Actually, this is kind of a pattern for me as I did the exact same thing for the IDE and other projects.

Python(x,y) was a great way of promoting Python for Windows users, and of sharing my work with the community on the matter of library selection - that was (and still is) an underestimated aspect of the work behind a distribution. Distributing packages means making choices (to avoid conflicts, redundancies, etc.), and it also means testing, documenting, and maintaining packages. It was a lot of work, but it was worth it.

However, a few years later, Python(x,y) was discontinued because of the technical difficulties of maintaining it. Initially, the distribution was based on quick and dirty scripts that were not scalable. Maintaining it for a single Python version (2.7, 32-bit) was already a lot of work, but maintaining it for multiple Python versions (2.7, 3.4, 32-bit, 64-bit) was impossible.

That’s why, in 2012, I created a new distribution named WinPython. The idea was to provide a portable, lightweight distribution that would be easy to install, easy to use, easy to maintain, and capable of deploying multiple Python versions side by side. The distribution was shipped with Spyder as the default IDE, and it was providing a lot of scientific libraries out of the box. It was a great success, and it was used by many users around the world. The project is still active today, and it is maintained by StoneBig. I left the project in 2014, but my teams at Codra (where I work now) are intensively using it for all our Windows-based scientific projects.

One IDE to rule them all#

The success of the migration from MATLAB to Python for developing applications was not only due to the Python language itself, nor to the scientific libraries available, nor to the libraries we developed, nor to the distribution we created. It was also due to the choice of the right IDE. Or rather, the development of the right IDE.

At that time, in 2008:

There was no integrated environment for Python that was as powerful as MATLAB. There were a few IDEs available, but none of them was suitable for both R&D and application development. The main issue was the lack of integration between the editor, the console, the help system, and the debugger. The workflow was not as smooth as it was in MATLAB.

Basically, either you were using IPython in a terminal for your interactive data processing and visualization, or you were using an IDE for developing applications (like Eclipse with Pydev). But, there was no IDE that was providing a good integration between the two worlds.

That’s why I started developing GUI components that will become the core of Spyder many months later.

So, my initial workflow was to use IPython for interactive work, and Eclipse with Pydev for application development. It was not very convenient, but it was the best I could find at that time.

Then, without thinking about creating an IDE, I started developing a few GUI components:

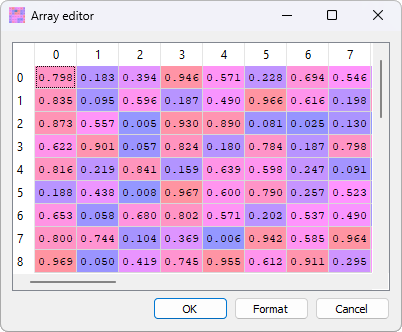

I remember that I was missing a MATLAB-like variable explorer, so I developed one. First, I wrote a NumPy array editor based on PyQt (this is still the widget used in Spyder for editing NumPy arrays), because viewing image data in a text editor was not very convenient. Then, I wrote a simple variable explorer that was able to display the content of the current namespace. One at a time, I added support for all the basic Python types (int, float, str, list, tuple, dict, etc.). It was a very simple widget, but a huge step forward for my workflow: viewing and editing variables in a GUI was far more efficient than using the console (not only you have an instant overview of the data, but you can also edit it in a more user-friendly way).

Array editor in Spyder#

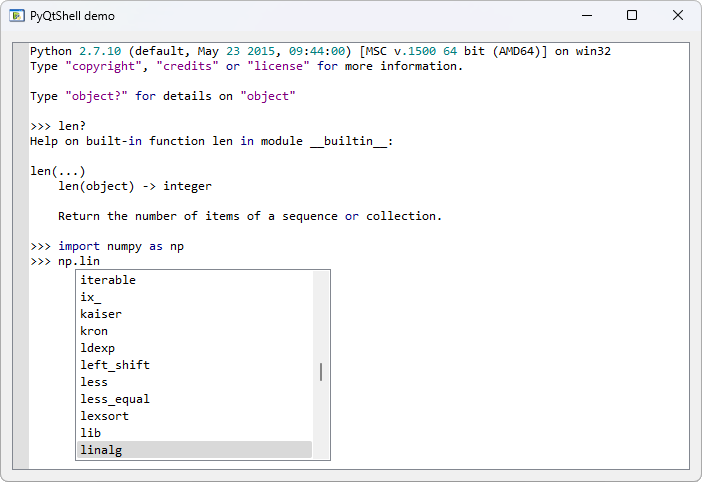

Then, I developed a Qt-based interactive console. The idea was to create an extension to PyQt that would provide a console application based on independent widgets interacting with each other. The project was named PyQtShell: my original post on PyQt mailing list is still available here. The main component was QShell, a Python shell with useful options (like a ‘-os’ switch for importing os and os.path as osp, a ‘-pylab’ switch for importing matplotlib in interactive mode, and so on) and advanced features like code completion based on QScintilla. I also implemented a CurrentDirChanger widget that showed the current directory and allowed to change it. I had plans for additional widgets like GlobalsExplorer (for showing and editing global variables), FileExplorer, CodeEditor, and others, but they were not implemented at that time. It was a very simple console application, but it was a huge step forward for my workflow: having an interactive console in a GUI with integrated widgets was far more efficient than using a terminal (not only you have syntax highlighting and code completion, but you can also integrate it with other GUI components, like the variable explorer).

PyQtShell interactive console#

Besides, I started developing a simple code editor based on QScintilla, to which I then added features like class and function browser, code completion, and so on.

At that time, I was not thinking about creating an IDE. I was just developing components that were missing in my workflow. But, little by little, I realized that these components could be integrated into a single application, providing a smooth workflow for both R&D and application development.

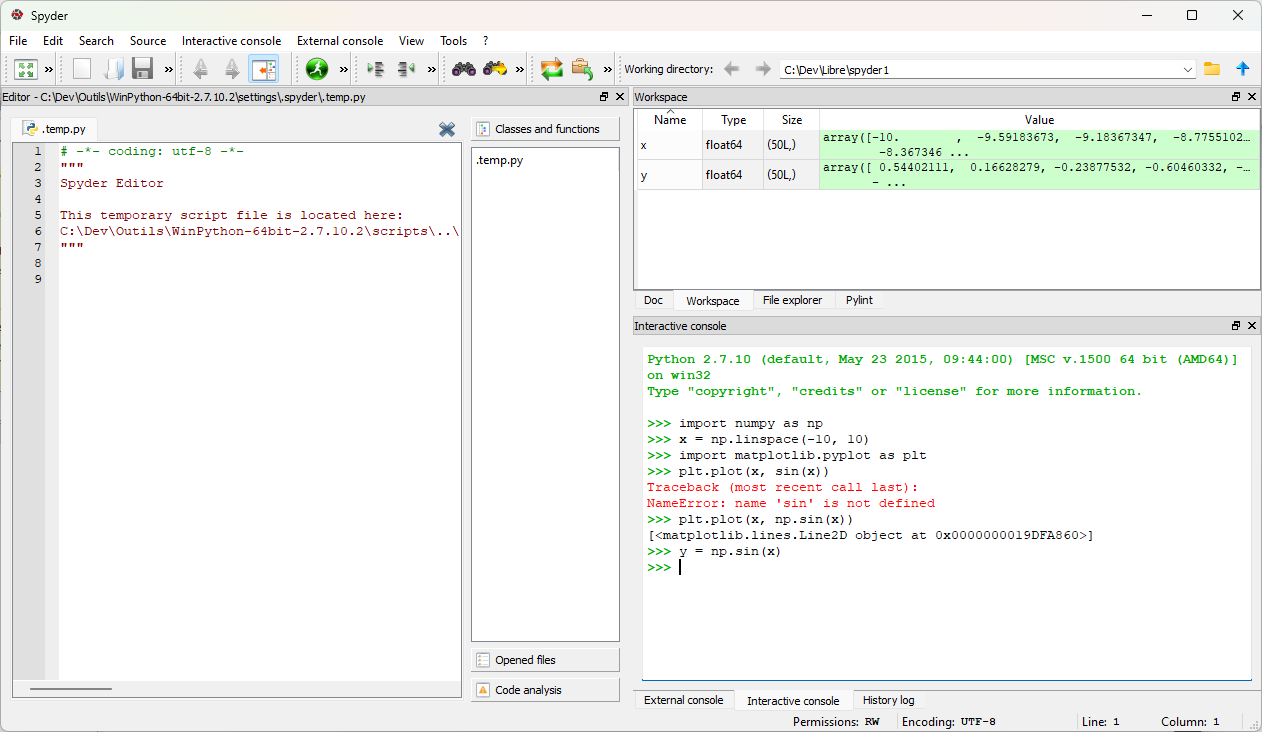

That’s how the idea of Spyder was born. I started integrating these components in early 2009: in January with PyQtShell demo 0.0.2, then adding the array editor in April, the external console in May, and the class browser in June. By July 2009, I released Pydee 0.4.23 - “Pydee” being the initial name for what was described as “a Python development environment providing MATLAB-like features in a simple and light-weighted software”. Pydee was part of pydeelib, a Python module based on PyQt4 and QScintilla2. The archived project is still available here.

Pydee Splash Screen (the background image is a photo taken by me at my in-laws’ - branches of an apple tree in spring time)#

In August 2009, as Pydee 1.0.0beta1 was ready for release, I renamed the project to Spyder (for Scientific PYthon Development EnviRonment). Spyder 1.0.0beta1 was released on August 10, 2009, followed by beta2 on August 14, and the first stable version Spyder 1.0 was released in October 2009.

Spyder 1.0 Splash Screen (again, the background image is a photo taken by me at my in-laws’ - a spider web, with a hedge in the background)#

Spyder 1.0.0#

So, Spyder started small, as a personal project to try and improve the user experience for scientific computing in Python. But, it quickly grew into a full-fledged IDE, thanks to the adoption by the community and the contributions of many users and developers. Today, Spyder is one of the most popular IDEs for scientific computing in Python, with a large user base and a vibrant community.

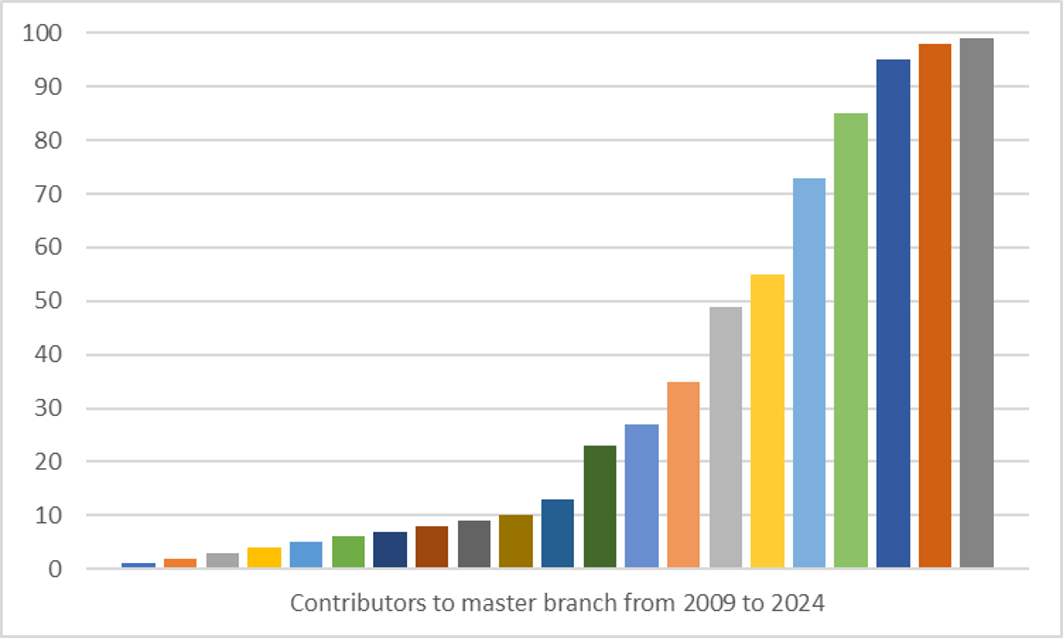

Spyder Contributors, from 2009 to 2024#

Note

In 2012, I progressively handed over the leadership of the Spyder project to Carlos Cordoba. Carlos was already a major contributor to the project, and he was the perfect person to take over the leadership. Since then, Spyder has continued to evolve and improve, thanks to the dedication of Carlos and the entire Spyder team.

About people#

Spyder would not be what it is today without the contributions of many people. Not only Spyder has been a tremendous technical learning experience for me, but it has also been an incredible human adventure with great encounters.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of people who contributed to Spyder in its early days (2009-2014), in addition to Carlos Cordoba (who took over the leadership of the project in 2012):

Ludovic Aubry (01-2009)

Phil Thompson (08-2009)

Alexandre Radicchi (09-2009)

Tim Michelsen (09-2009)

Frédéric Picca (11-2010)

Carlos Córdoba (12-2010)

Jed Ludlow (01-2012)

Sylvain Corlay (01-2014)

And more recently, I had the pleasure to meet in person some of the current Spyder contributors at SciPy conferences:

C.A.M. Gerlach (at SciPy 2024)

Juanita Gomez (also at SciPy 2024)

Without them, and without all the active users who reported bugs, suggested features, and contributed to the documentation, Spyder would not be what it is today. It would have stayed as proof-of-concept software, used only by me and a few others. Because the short-term motivation for developing Spyder was to improve my own workflow (also, it was so fun to do!), but the long-term motivation was to create a tool that would be useful for the community. So, a big thank you to all of them!

About the logo#

I designed the first Spyder logo myself, in 2009, using Inkscape. I wanted to create a logo that was simple, recognizable, and that conveyed the idea of a spider web (no other intended meaning than the phonetic similarity between “Spyder” and “spider”) with a Python inside.

Spyder 1.0 Logo#

The very same logo was used until Spyder 5, that is for more than 10 years. In 2020, for the release of Spyder 5, Isabela Presedo-Floyd designed a new logo that is still used today. The idea was to keep the same concept, but to modernize the design and to make it more appealing. The new logo required a lot of iterations and discussions (see for example this issue on Spyder’s GitHub repository), but the final result is great.

Spyder 5 Logo#

ℹ️ For the record, I was not involved in the design of the new logo, as I had left the Spyder project a few years earlier. And when Carlos Cordoba (the current lead maintainer of Spyder) asked me for my opinion on the new logo, I was very reluctant at first - I was attached to the old logo, and I was not sure that a new logo was necessary. Then, after a while, I realized that the new logo was a great improvement, and I fully supported the change. Maybe a part of me was not ready to let go of Spyder, after all these years of involvement in the project…

Conclusion#

Looking back at Spyder’s origins, what started as a personal quest to find better tools for scientific application development grew into something much larger than I could have imagined. The decision to switch from MATLAB to Python in 2007 was risky - I was alone in a 300-people Department advocating for a language that was far from mainstream in scientific computing. But the bet paid off, not just for my team at the CEA, but for countless scientists and engineers around the world who found in Spyder a familiar yet powerful environment for their work.

Spyder’s creation was never planned as a grand project. It emerged organically from real needs: a variable explorer here, an interactive console there, a code editor with the right features. Each component was built to solve a specific problem in my daily workflow. The beauty of open source is that these personal solutions can become community tools, and Spyder became exactly that - a tool born from necessity, shaped by community feedback, and refined through years of collective effort.

Today, Spyder has far outgrown my initial contributions. Under the leadership of Carlos Cordoba and the dedication of the current team and contributors, it continues to evolve and adapt to the changing landscape of scientific computing. While I’ve moved on to other projects like DataLab, I’m proud of what we built together and grateful for the community that embraced it. Spyder proved that with the right tools, Python could not only match MATLAB for scientific work - it could surpass it.